Fashion as Power

Throughout history, rulers have used clothing not merely to dress, but to declare who they are. For the Ottoman sultans—leaders of an empire that spanned over six centuries and three continents—clothing was a language: a symbolic, ceremonial, and strategic tool. Each robe, turban, and accessory was infused with religious symbolism, imperial ideology, artistic sensibility, and international influence.

In this article, we dive deep into the secrets behind Ottoman imperial clothing, from symbolism and construction to foreign influences, functional changes, and historical evolution.

Materials and Craftsmanship: The Fabric of Empire

Raw Materials

Ottoman imperial garments were made of luxurious materials sourced both locally and internationally:

- Silk: Primarily from Bursa and Damascus, dyed and woven with extreme delicacy.

- Cotton: Grown in Egypt and Anatolia, used for underlayers and linings.

- Gold and silver thread (tel): Spun with silk into brocades known as seraser, kemha, or diba.

- Fur: Imported sable, lynx, or ermine lined winter kaftans—status markers of high rank.

Weaving Techniques

Ottoman fabrics featured incredibly intricate weaving techniques:

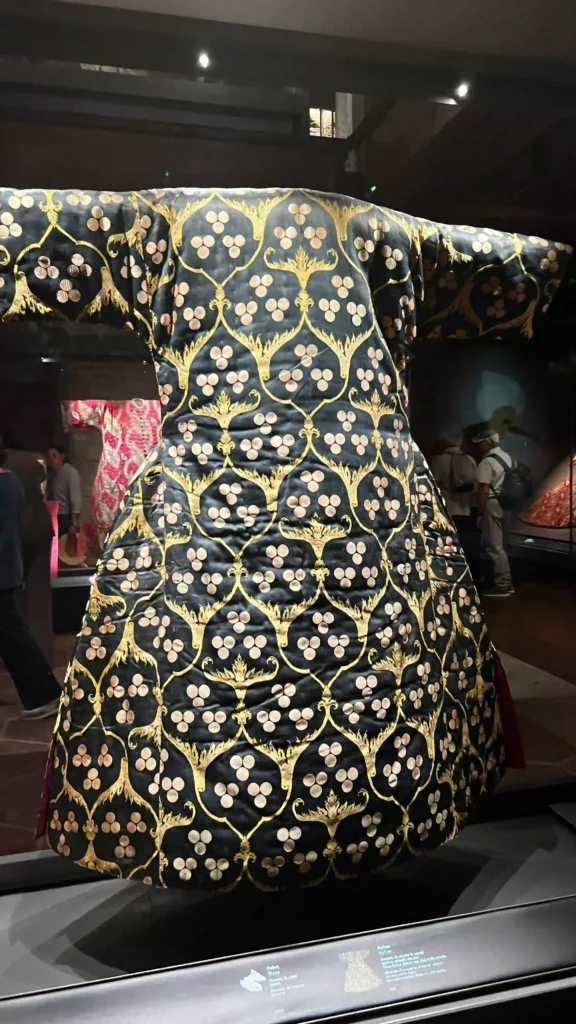

- Kemha: A type of velvet brocade with raised floral or geometrical motifs.

- Seraser: A silk-based brocade with gold or silver woven patterns.

- Kutnu: A colorful silk-cotton blend, often striped, used in later periods.

- Lampas and satin weaves were also common for ceremonial garments.

Much of this work came from state-sponsored weaving centers, such as those in Bursa, Istanbul, Aleppo, and Cairo, ensuring both luxury and loyalty.

Symbols and Motifs: Clothing as a Sacred Script

Why So Many Patterns?

Ottoman garments were symbolic uniforms. The sultan wasn’t just a ruler—he was the Shadow of God on Earth(Zıllullah fi’l-arz). His garments reflected divine authority and universal kingship.

Key Symbols:

- Tughra (Imperial Monogram)

Often subtly woven or embroidered into fabric, the tughra served as a spiritual signature of the sultan—like wearing his own divine identity. - Cloud Bands (Çintamani Motif)

Borrowed from Chinese-Mongol traditions, often appearing as three dots above wavy lines, symbolizing power, vision, and luck. - Lotus, Tulip, and Carnation Motifs

Deeply embedded in Islamic art:- Tulip (Lale) is an anagram for “Allah” in Ottoman Turkish and represents monotheism.

- Carnations stood for divine beauty and paradise.

- Lotuses, often symmetrical, indicated cosmic harmony and eternity.

- Stars, Moons, and Suns

Astronomical symbols were linked to timekeeping and divine order. The Sultan’s legitimacy was seen as cosmic destiny. - Calligraphy Bands (Tiraz)

Worn around cuffs or across the chest—usually contained Qur’anic verses, blessings, or praise for the reigning sultan. - Color Symbolism:

- Red: Nobility, reserved for the sultan and top elite.

- Blue and Green: Spirituality, tied to Islam and nature.

- Black and Gold: Authority and divine light.

- White: Purity, often worn during religious events.

The Evolution of the Kaftan: From Wide and Regal to Slim and Modern

Early Period (14th–16th centuries)

- Loose, voluminous kaftans with wide sleeves, generous length, and multiple layers.

- Inspired by Central Asian Turkic styles and Ilkhanid-Mongol court fashion.

- Functioned as both garments and mobile thrones—the wearer looked immovable and commanding.

Mid Period (17th–18th centuries)

- Fabrics became even more ornate as wealth increased. Imperial kaftans used layered brocades.

- The cut began to slim down—aesthetic preference shifted toward a more elegant, upright silhouette.

Late Period (19th century – Tanzimat Era)

- With Europeanization reforms, kaftans grew shorter, lighter, and more tailored.

- The entari and setre (closer-fitting jackets) replaced loose kaftans in many contexts.

- Ottoman fashion was increasingly influenced by French, Austrian, and Italian tailoring styles.

- Some sultans even wore Western-style trousers and jackets, blending Ottoman tradition with European dress codes.

Headwear: From Turban to Fez

Turban (Saray Sarığı)

The turban was one of the most iconic symbols of the sultan and his court. A master of symbolism, the turban conveyed:

- Religious authority (connection to Islamic scholars).

- Rank (number of wraps, height, and fabric determined status).

- Protection: Some had metal inserts for defense in combat.

Each janissary unit, court official, and religious group had a distinct turban style. For example:

- Sultans wore towering turbans with fine muslin.

- Viziers had layered wraps around a base cap.

- Judges (kadı) wore flatter, more scholarly wraps.

Fez (Fes)

In the 19th century, the fez replaced turbans during the reforms of Sultan Mahmud II (r. 1808–1839).

- Symbolized modernization and equality—everyone wore the same basic headgear.

- Inspired by North African dress, especially from Morocco.

- Criticized by some for breaking tradition but embraced by reformists for its Western-friendly appearance.

Later, the fez itself was banned under Atatürk during the Republic era, marking a full shift away from Ottoman identity.

Foreign Influences: East Meets West

The Ottomans stood at the intersection of Europe, Asia, and the Islamic world, and their clothing reflected this unique position.

Influences:

- Central Asia: Original kaftan design, fur-lined robes, and nomadic tailoring.

- Persia (Safavid Empire): Color schemes, floral motifs, luxury silk traditions.

- Byzantium: Ceremonial dress codes and imperial color symbology.

- China: Use of silk weaving techniques and motifs like cloud bands or dragons (adapted into Ottoman versions).

- Europe: Especially during the Tanzimat era, Ottomans imported French fashion, tailors, and even garments.

The Ritual of the Robe: Hil’at

Garments were not only worn—they were awarded.

When a general, ambassador, or foreign ruler pleased the sultan, he would receive a hil’at (robe of honor). This was:

- A political message: “You serve under the Sultan’s shadow.”

- A legal seal for appointments: No post was official without the robe.

- A religious blessing: Tied to the Islamic tradition of giving garments (sadaqa).

Some robes were passed down, becoming relics. Others were gifted as part of diplomatic kits (safra hil’ati).

The garments of the Ottoman sultans were more than imperial luxury. They embodied a cosmic vision of rule, where every thread echoed divine order, and every fold carried centuries of cultural fusion.

From Central Asian nomadic roots to Mediterranean court traditions and Persian aesthetic philosophy, Ottoman clothing was a tapestry of civilizations—a wearable symbol of empire.

Today, these garments are preserved in Topkapı Palace, offering not just a view into past fashion, but a living story of one of the world’s most sophisticated and symbol-rich empires.